-

A Sex Positive Asexual

July 23, 2014Before I started watching the BBC cult hit Torchwood, well-meaning friends and acquaintances told me I...

-

Viet Pride 2014, Starting 18th July!

July 16, 2014Starting from the end of 2013 until now, we have witnessed positive movements in the gay,...

-

The HIV Stigma

July 15, 2014The HIV Stigma: How do millennial gay men deal with HIV and the persistent social stigma...

-

The invisible LGBT people in ASEAN: Part 3

July 6, 2014Discrimination of sexual minorities in ASEAN akin to a dog chasing its own tail. We can...

-

Pink Dot SG : A Celebration of Diversity

July 6, 2014Pink balloons gather and aflutter; nothing short of spectacular. The sixth annual Pink Dot SG was...

-

The invisible LGBT people in ASEAN: Part 2

July 5, 20142. The least developed: Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar Known as CLM, the trio is far from...

-

The invisible LGBT people in ASEAN: “This is our lives we are talking about!”

July 5, 2014A transgender girl baring her breasts against the military coup in Thailand, marked with pro-democratic slogans and...

-

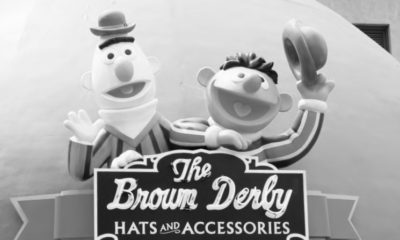

Are Bert and Ernie Gay? :)

June 28, 2014Bert and Ernie. Gay? Why is this important? I was horrified to read years ago that...

-

I Do, Do You?

June 25, 2014Being a gay guy with quite a fair bit of failed relationships does not mean that...